The acquisition of language in a child has got to be one of the most fascinating processes to witness for any parent. Most parents are awed by the sudden burst in the proficiency of their child's language. Going from barely acknowledging the understanding of a simple word, the child learns to converse fluently within a span of just a few years - a feat even a supercomputer cannot achieve at the time of the writing of this post. The most fascinating parts are the early stages of this process where the child just begins to posit a structure to the environment around it. The process of generalization can only become easier during the later phases, because the child can always bootstrap.

The acquisition of language in a child has got to be one of the most fascinating processes to witness for any parent. Most parents are awed by the sudden burst in the proficiency of their child's language. Going from barely acknowledging the understanding of a simple word, the child learns to converse fluently within a span of just a few years - a feat even a supercomputer cannot achieve at the time of the writing of this post. The most fascinating parts are the early stages of this process where the child just begins to posit a structure to the environment around it. The process of generalization can only become easier during the later phases, because the child can always bootstrap.Debates on the process of acquisition start from the very birth of the child. The most fundamental debate is on whether there exists a special faculty or conceptual organ developed for language. The school of thought lead by Noam Chomsky believes in such a dedicated faculty, leading to the concept of a Universal Grammar. The argument supporting this idea is that children manage to restrict their grammar in the absence of negative examples and explicit correction. It has been proved that even regular languages are unlearnable under such conditions, and natural languages are known to be atleast context-free. The opposition, most strongly voiced by Michael Tomasello, considers language to be a complex system that is handed down from generation to generation, with absolutely no genetic adaptation. They of course have their own arguments, and computational linguists like Simon Kirby have designed very interesting simulations to support it.

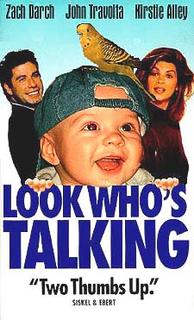

Let's get back to our protagonist of this article, shall we? - the child , still a baby as of now.

The first thing that every parent waits for is for the baby's first word. The process of acquisition obviously starts with single words. How does a child learn its first words? You must realize that determining this is not as simple as it seems. Associating a word with a concept requires many sensory and cognitive processes. Firstly, the child must be able to segment the verbal input phonologically in order to distinguish a word. The child is also just then forming the conceptual map in his head, and must successfully associate these recognizable sounds with the concepts in its head.

Rather cute (and cute-sounding) experiments like High-Amplitude Sucking have shown that babies can hear the full range of sounds as adults and can distinguish between sounds just as finely. All the baby now needs to do is recognize patterns in the sounds and realize that they are to be mapped to certain concepts. Studies show that infants like humans in general have the inborn ability to recognize repeated patterns. It has been suggested that motherese, the way adults speak to babies with a lot of melody and intonation, helps the baby pick up patterns better. Given this toolset, the infant starts mapping these patterns to concepts. It is obvious that it first learns words that have meanings that it can easily map - physical objects around him (duckie, table), people around him (mom, dad), events (drink, eat) etc. It is also known that a baby understands many words even before it starts producing them.

The child eventually begins to use these single words to express more complex concepts. For e.g. it might say 'cup' to express 'I want the cup' as well as 'I can see the cup'. This expression of more complex thoughts also implies that the baby is positing a structure to the world around it. The single-word phase then matures into a two-word and then a multiword phase. Utterances like 'daddy good' and 'water no' mature to 'where wrench go? '.

Steven Pinker suggests that infants generalize utterances into an early grammar using verb meanings. These verb meanings are learnt from observation. Lila and Henry Gleitman think that the exact opposite is at play - the child learns the meanings of verbs using the early syntax that it learns from pure pattern recognition. Perhaps both processes go on - both Pinker and the Gleitmans have later acknowledged that this is indeed possible. One interesting fact is that although children make mistakes in morphology (e.g. 'can i keep the screwdriver like the mechanic keep the screwdriver?'), they almost never make mistakes in word order.

Once a basic grammar is formed in the child's head, it can move on to conquer exceptions like irregular verbs, idioms and the sort. Utterances like 'I goed to the market' are heard often enough from children. However, all becomes fine and dandy soon, and the child starts speaking just like an adult. The only process of acquisition that goes on beyond the critical period (ending at puberty) is that of lexical acquisition, which goes on as long as the individual is interested!

13 comments:

A very detailed post.. really informative. But it still leaves me unanswered as to how does a child differentiate between two totally different language sets? The post clarifies about the natural learning process, but what if the child belongs to a multilingual society as in India?

Thanks!

And yes, that's the other question you guys asked, and it deserves a post all of its own. Also, I want to write about education in India and multilingualism, something I was given a flavour of sometime back...

Wait till my next post.

"children manage to restrict their grammar in the absence of negative examples and explicit correction"

What do you mean by negative examples and explicit correction? I went through a bit of Chomsky's literature, but couldn't figure that out.

And don't you feel the concept of Universal Grammar in itself is arguable?

I mean that parents don't concentrate on actually correcting a child's language or listing out incorrect sentences until much later in the acquisition phase.

For example, if a baby starts saying 'milk nomore' to express that the milk is finished, you wouldn't expect parents to explain to him that it's a wrong construction or tell him the right utterance. In most cases, the parents start speaking like the baby instead!

Universal Grammar is simply a formalization of the concept that we all are programmed with some constraints of language. This is reflected in the fact that many mechanisms are common in all languages as well. One quoted example is...

Morphological derivations have a certain order of application. Consider the plurality modifier 's' and the derivation 'ism'. Notice that the 'ism' is always closer to the root word compared to 's'. i.e. 'darwinisms' is valid, but 'darwinsism' is invalid. Now you'll be surprised to know that this is common in all languages - derivation before plurality!

Many more commonalities like this seem to support that we all have some implicit constraints within us.

Wonly one question...do children also use Wren and Martin and learn that starting a sentence with gerunds/conjunctions is bad practice??

The Wikipedia definition of Universal language says exactly the opposite! And that's where I am confused.

"This theory does not claim that all human languages have the same grammar, or that all humans are "programmed" with a structure that underlies all surface expressions of human language."

Isn't it totally contrasting your explanation?

Whatever complex (I didn't get a shit of the technical jargon you have used :( ) example you have given, or any logical conclusion would suggest the same - i.e. all the languages in the world seem to be governed by some superset of language construct, and that's why the term Universal Grammar.

But if so, then why don't all the languages in world have a common set of rules? And the most confusing of it all - why does Wikipedia or Chomsky round it up only for Children and not the whole set of language?

And I had one more doubt - slightly different than the present context. How does an infant differentiate between noise and meaningful words? What makes it giggle when someone makes a pleasant sound and makes them cry when some noise is there?

Noise and music are not goverened by any grammatical or syntactical law!

@kanishka: Bad practice and badly formed sentences are two different things.

@Keshav: The very next line from Wiki says: "Rather, universal grammar proposes a set of rules that would explain how children acquire their language(s), or how they construct valid sentences of their language."

Well, this is what UG is. It gives a list of constraints under which natural language becomes learnable; constraints without which no learner would be able to learn in the absence of -ve examples and correction!

Although UG does not claim it, this commonality obviously implies some homogenity in all our genetic makeup, doesn't it?

@keshav: An infant learns to differentiate between meaningless noise and words due to repeated exposure of the words. Plus, it gets other cues, right? Parents' eyes are focused on the children and their lips move as they speak...

About the other doubt, that's a more fundamental concept, not linked to language at all. What makes sounds pleasant and unpleasant? It's similar to asking why we call some smells fragrances and others stink. No idea. Just the way we are made...

I agree to some extent.. but am not fully convinced! There is some doubt confusing me but can't exactly articulate what is it.

And regarding your example of fragrance and stink.. I have always wondered what made humans differentiate between the two extremes- Music/Noise, Beauty/Ugliness, fragrance/stink? Just like our other judgements are based on our senses, and the capability of the brain to parse those, even these must be guided by some rule!

@keshav:

I missed out a point - regarding your question about why all grammars of the world are not the same.

UG defines a subset of all possible languages that are learnable, that's all. It's like isolating a subset of CFGs (debatable... languages could be CSGs or more) and saying that these are learnable by humans and these aren't. Of course, this learnability is under the constraints I mentioned earlier (no -ve examples).

So, the grammar of Hindi and English, for example, are both learnable by humans. It's just that one of them gets picked by the learner because of what's around him.

P.S: Wikipedia is unreliable :P

Interesting! Long ago when i didn't understand computer networks (of course its different now :P), i had this fantasy of being able to get into a wire (i know!) and follow the bits around. Now i wanna get into a child's head and see!

I am a firm believer that the latter is indeed possible! :)

About the former... hmm... perhaps you'd like to contact braman@? :P

Post a Comment